Same city, same art crowd, same pool of donating collectors. Same dollars from tourists. Same membership dues from locals. What used to separate the Art Institute and the Museum of Contemporary Art was the art. The Art Institute prided itself on having a classic collection of masterpieces, and the MCA featured stuff so bizarre that visitors couldn’t tell the art from the humidity monitors on the floor. But with the Art Institute’s Modern Wing opening, the lines just got blurred.

In terms of collections, the Modern Wing would intimidate any rival. It’s the envy equivalent of your ex showing up with a Scandinavian supermodel, accessorized with a degree from Harvard and a double-D endowment. But if the Art Institute is a brainy supermodel, then the MCA is that model’s younger, more rebellious sister. While the Modern Wing houses an encyclopedic set of masterworks designed to educate the public on art made in the early 20th century and beyond, the MCA continually has redefined what it means to be an art institution since it opened in 1967. Early MCA exhibitions included Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapping the inside and outside of the building in cloth, and more recently, pairs of lip-locked dancers re-enacting famous kiss paintings for a Tino Sehgal piece in 2007. “The core of our program is a convergence of exhibitions, performance and education,” says Madeleine Grynsztejn, director of the MCA. “We aim to instigate an exchange of ideas.”

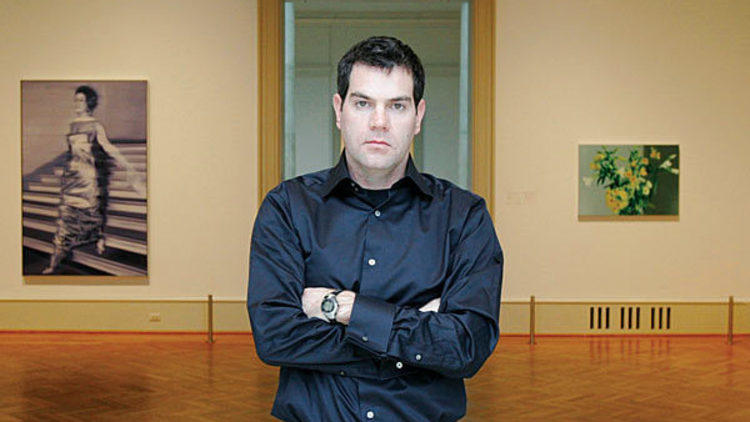

But that doesn’t mean the Art Institute won’t do a little instigating of its own. James Rondeau, one of the contemporary art curators of the Modern Wing, says he has plans to match the MCA by featuring temporary commissioned exhibits. “There’s lots of overlap [between the MCA and Modern Wing],” he says. “People think that the Art Institute won’t be showing young art, but that’s not true.” He acknowledges the perceived rivalry between the museums, but counters that “healthy competition is good for everyone” and that the Modern Wing will improve Chicago’s place in the art world, which also will benefit both institutions. “Our success is their success, and we’ll each do things in our own way.”

Forty years ago, relations between the two museums weren’t exactly so chummy. “The Art Institute threw every stone in [the MCA’s] path trying to block it [from happening],” contends veteran art collector and gallerist Richard Feigen. “But I think it was the creation of the MCA that got the Art Institute to collect more contemporary art.”

Feigen recalls one of the early stumbling blocks when he helped lead the effort to start a second art museum in the late 1950s. He and other collectors formed a corporation called the Gallery of Contemporary Art that attempted to purchase the U.S. Court of Appeals building at 1212 North Lake Shore Drive, which the feds were selling for $1, to serve as the museum. According to Feigen, an Art Institute trustee squashed the collectors’ efforts by interceding at the mayor’s office and preventing them from getting the building. (When asked about this, the Art Institute had no comment.)

Bad blood there? Sure. But then there’s the folklore that anti-Semitism at the Art Institute spurred the creation of the MCA. A longtime rumor circulating in the art world contends that Jews weren’t allowed on the board of trustees of the Art Institute. Yet Leigh Block was Jewish, elected in 1949 and promoted to chairman of the board in 1972. Block, however, was the exception, as the vast majority of the board was gentile. Feigen’s book, Tales from the Art Crypt, chronicles Leigh Block’s reign at the Art Institute and describes the social climate in the ’50s, when Jews were banned from the social elite, from the grand apartments on Lake Shore Drive to the entire town of Lake Forest. At that time, according to Feigen, young Jewish art collectors felt that they, and their art collections, weren’t welcome at the Art Institute. (Once again, the Art Institute offered no comment.)

It was two of those collectors—Joe Shapiro and Lewis Manilow—who created the MCA. By the time the museum opened in the late ’60s, however, times had changed; Jews had gained more acceptance. “[By then,] it was all about the art and nothing about religion,” Manilow says. “Our focus was the creation of a museum committed to the art of its day, to the living artist.”

The two museums still weren’t completely at ease with each other, of course. But much of the tension dissipated when James Wood took the helm of the Art Institute in 1980. Manilow recounts how “Wood gathered together members of the MCA board and Art Institute board and said, ‘I don’t care who gets the [donated] art, as long as it stays in Chicago.’?”

Since then, the institutions have shared trustees and board members, and even staunch MCA champions like Feigen are Art Institute benefactors today. When asked whether the museums are still rivals, Manilow laughs. “I would be flattered to be seen as a rival to the Art Institute—it’s a magnificent institution. We were the little guy, lucky to survive.”

But then he muses about the MCA building a new wing of its own. “[I’d] love to imagine it,” he says.

The Art Institute, on the other hand, would probably rather not.

Don’t forget the “old” Art Institute building—there are plenty of changes going on there, too.